Elon Musk has yet to change life on Mars, but the man has changed life on our planet forever.

We know about the cars, rocket ships, and tunnels; Ludicrous, Twitter, and Grimes. But for all of Musk’s ventures, including Tesla producing and delivering 1.3 million EVs globally in 2022, his most underrated breakthrough may be Tesla’s biggest modern edge: the Supercharger network.

This story originally appeared in Volume 14 of Road & Track.

“Without the Supercharger network, we wouldn’t be talking about Tesla today,” says Dan Ives, a Wall Street tech analyst and regular television commentator on Tesla and EVs. “It was the core DNA of their success, along with innovation and engineering. Now it’s the linchpin of their brand and their competitive moat against other automakers.”

Tesla Hatched The Egg; Rival Automakers Were Chicken

For the fledgling Tesla of roughly 2008 to 2012, life-or-death priorities included developing the Model S and opening a California factory. Then there was solving fiendish battery riddles, plus managing an IPO, Wall Street, and the government. Musk staved off personal bankruptcy as he poured $55 million into the company by 2008, even as he pushed SpaceX toward liftoff.

Considering all the Hail Mary plays, it’s striking that Musk & Co. could draw up one more for a far-flung global charging network. But from the early days, executives including JB Straubel, the chief technical officer Musk considered a co-founder, saw game-changing potential.

“JB was always stoked about the idea of charging fast,” says Troy Nergaard, a former Tesla senior engineer who led Supercharger development. “We were all excited about getting power into the car quickly, if the battery could accept it.”

Current and former Tesla employees recall chaotic yet inspiring times. Even as incumbent automakers scoffed at the Silicon Valley upstart, Tesla solved the chicken-and-egg conundrum that kept EVs in an embryonic state by birthing car and charger simultaneously. Charger prototypes sprung from a company lab in Palo Alto. California’s first six Superchargers, erected starting in 2012, stacked a dozen of the Model S’s 10-kW onboard chargers. That ingenious modular design, Nergaard says, may explain some of the Supercharger’s reliability advantage over competing chargers. “The core of the Supercharger is the core of the vehicle, and fast-charge makers who don’t come from an auto environment don’t necessarily have that rigor,” Nergaard says.

Along with Tesla’s wizardly innovations in batteries, software, and controls, the sleek Superchargers pushed free DC electricity into the groundbreaking sedans at unheard-of speeds, courtesy of 90 kW of charging power.

“We knew we could charge at faster rates than had ever been done,” says Ali Javidan, a former Tesla engineer who led prototype R&D. “We knew road trips were a big deal, not just because of the family fantasy, but because that’s a decision-maker in car buying. So we started choosing our favorite corridors and putting in Superchargers.”

In October 2011, Nergaard and his team put bare-bones Supercharger prototypes, electronic guts still showing, through their paces at Tesla’s Fremont factory. Tesla invited early reservation holders for Model S ride-alongs, which required quick charges to keep the amusement rides going. “That was the first time we tried charging multiple vehicles back-to-back,” Nergaard says.

On the morning of September 24, 2012, Nergaard’s engineering team set out from Folsom, near Sacramento, in a pair of Model S cars. It was history’s first fast-charging long-distance EV road trip, like Thelma & Louise minus explosions. “It was so fun to see it function in the wild for the first time,” Nergaard says. That afternoon, the team rolled into Tesla’s design center in Hawthorne, near Los Angeles, in time for Musk’s public reveal of the network. The era of long-distance EV driving had begun, soon to sweep the globe.

That evening, Musk, wearing a black “Supercharger” T-shirt, bounded onto a stage, flanked by a roughly 20-foot obelisk and smothered in rock-concert smoke. This was ostensibly the Supercharger that Musk said would sprout along the world’s highways. In another now-familiar Barnumesque flourish, Musk declared the Superchargers, fed by his SolarCity panels, would generate enough juice to power every Tesla. “You’ll be able to travel for free, forever, on pure sunlight,” Musk told the delighted crowd.

Only a handful of solar Superchargers materialized. The overweening obelisk was never seen again. But Superchargers were real. Days after the reveal, a New York Times reporter drove a Model S 531 miles from Lake Tahoe to L.A. over 11.5 hours.

“The one big holdout with most EVs today is that you can’t take a road trip,” Straubel said at the time. “What happens if I want to go across the country? I can’t tell you how many times we get that question.”

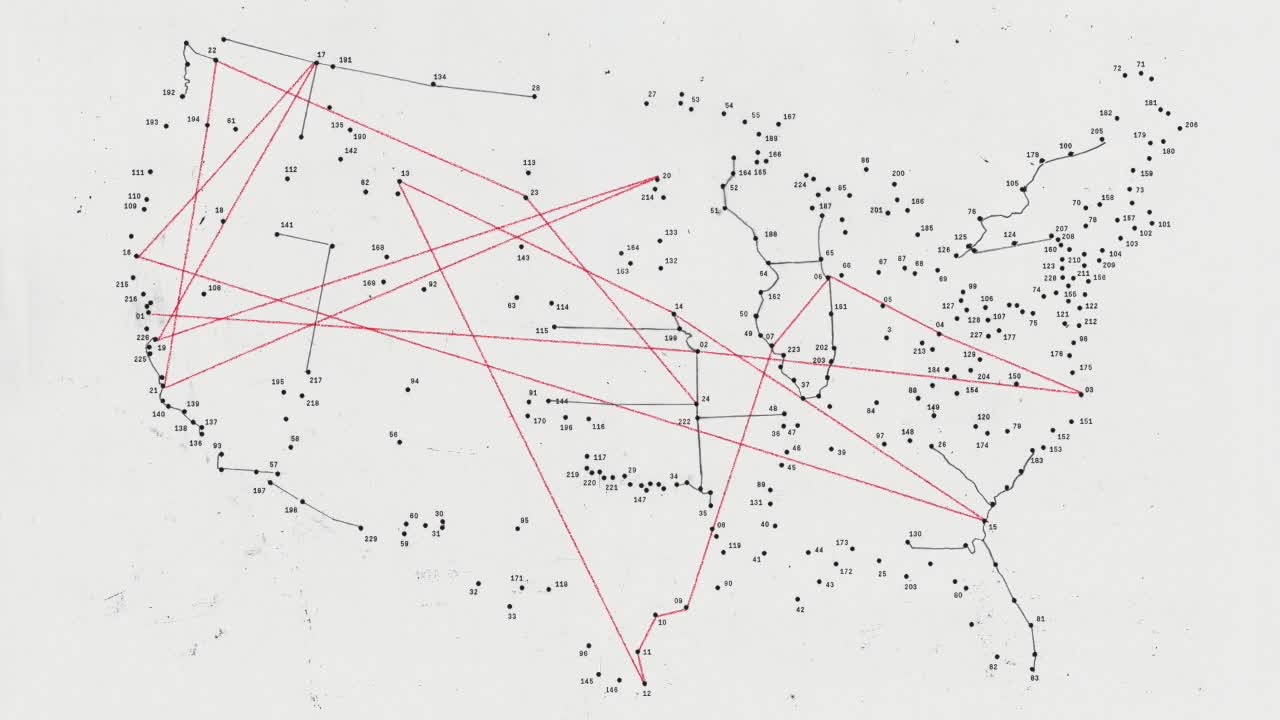

The question was answered. As of the third quarter of 2022, in the midst of a global expansion, Tesla has more than 4200 DC stations—almost 1700 in North America alone—with nine individual stalls per station on average. A June milestone saw the company open its 35,000th Supercharger stall in Wuhan, China. Earlier in 2022, Tesla erected a 14-stall Florida station using a clever new pre-assembly system in just eight days.

Halt and Catch Up

First-wave buyers needed the reassuring backstop of public charging. And not just early adopters: J.D. Power surveys show that charging anxiety, not range anxiety, remains the top barrier to EV adoption. Javidan calls the Supercharger network, which gives buyers coast-to-coast reasons to choose a Tesla over models from Ford, GM, Hyundai, or Volkswagen, “a perfect example of what makes Elon, Elon. He’ll say, ‘I can create a better user experience. So how can I force this future sooner?’ And he’s got the guts to say to engineers, ‘Pencils down. Let’s ship it to customers and make it better over time, even if there’s bad and good to that.’”

So why didn’t other automakers build or fund their own networks (Rivian is trying, as are Mercedes-Benz and Stellantis more recently) or cut some partnership with Tesla? Martin Eberhard, who co-founded Tesla in 2003—before Musk notoriously forced him out in 2007—suggests a few reasons. Volkswagen’s German EV department, where he worked post-Tesla, was a Siberia for engineering “losers,” he says. They were tasked with making dreadful compliance cars to help the company prove the pointlessness of EVs, in Eberhard’s view. “It was clear people at the top didn’t buy into it at all,” he says. As for chargers, that kind of holistic problem-solving “is outside automakers’ paradigm. To them, that’s Chevron’s problem or whoever.”

Eberhard recalls a pointed dismissal from Wolfgang Hatz, Volkswagen Group’s imperious engine chief: “Mr. Eberhard, I am four years from mandatory retirement,” Hatz said. “By then, I guarantee 100 percent of our profits will come from internal combustion. So why am I talking to you?”

Hatz would spend nine months in a German jail beginning in 2017 for his role in Dieselgate, enough time to mull the irony: That sooty scandal sparked VW’s about-face on EVs. VW’s $2 billion U.S. settlement also birthed and funded Electrify America, one of several charging outfits that has failed to match Musk’s trustworthy plugs.

“Tesla has put the full force of the company behind the network as one integrated user experience,” says Chris Nelder, an energy author and analyst who has advised the White House on infrastructure. “No one else is approaching it that way, so they don’t have the same commitment.”

What Musk really cares about

It helps that in America, Tesla’s proprietary network must only be compatible with Tesla models (at least for now). Rivals wrestle with interoperability concerns. Seemingly every customer of Electrify America, ChargePoint, or EVgo can relate horror stories of malfunctioning chargers. A San Francisco survey of nearly 660 non-Tesla chargers found just 73 percent working properly. Others were unresponsive or had screen issues, broken plugs, or payment or network failures.

“Take a 400-mile road trip in a non-Tesla, and there are clear risks,” Ives says.

Spotty reliability, Nelder says, “has become a black eye on the industry. People need to feel that when they show up to a charger, it will work.”

Americans bought more than 330,000 EVs in the first six months of 2022, up from less than 15,000 in all of 2012. Many are taking a leap of faith: For nearly 80 percent of Ford F-150 Lightning buyers, the pickup is their first EV. At the Lightning launch in Texas, Darren Palmer, Ford’s EV vice president, acknowledged that charging’s “black eye” could ultimately bruise automakers who sold those EVs.

Ford has taken matters into its own hands, sending teams of “Charge Angels” to test stations, diagnose issues, and nudge partners to fix them, pronto. The initiative underscores vulnerabilities for automakers that don’t build and operate their own networks.

A Tesla pilot program in 13 European countries, where newer Teslas run a common CCS2 plug, gives owners of other brands a limited taste of Supercharging. Musk hasn’t pulled the trigger on this availability in the U.S., protecting his golden goose.

“Between Detroit, China, and everyone else, 100-plus automakers are going after the EV market. There’s no reason for Musk to play nice in that sandbox,” Ives says, even if monetizing often-idle, unprofitable chargers remains a vexing challenge.

Yet Javidan believes that Musk, determined to sprinkle EVs over the earth’s surface, may open the network to common Ioniqs and ID.4s, or be carrot-and-sticked into it by governments. Setting aside small numbers of Superchargers for non-Teslas—with premium pricing, slower speeds, or limited features—might be considered a civic responsibility, and it wouldn’t anger Tesla owners.

“He really cares deeply about these issues,” Javidan says. “I don’t see a scenario where he’d say no to the rest of the world.”

With plug installations lagging behind expected EV demand, the White House is mounting a $5 billion cavalry to spur construction of 500,000 chargers, part of the $1 trillion infrastructure bill. At Detroit’s recent auto show, vintage–Sting Ray owner President Joe Biden hopped into a Cadillac Lyriq, noted his preference for the Corvette Z06, then announced $900 million in funding for chargers in 35 states. While new plugs and jobs should be welcome, some question whether this public-private partnership will create serious Supercharger alternatives. Will it just waste money on companies, municipalities, or contractors with poor track records? Under the current plan, charging companies must achieve 97 percent reliability as a funding condition. Nelder advised the administration that oversight and accountability were in order but acknowledged that near perfection seems optimistic.

Eberhard suggests that rather than always trying to be “Tesla 1.1,” automakers and charging stakeholders should seek new ideas and unmet needs. Curbside charging for urban residents, who currently feel locked out of the EV game, is an obvious opportunity.

Mack Trucks or Musk Trucks?

The Department of Energy estimates that medium- and heavy-duty trucks emit a bit more carbon dioxide than all passenger cars combined. TeraWatt Infrastructure has quickly raised $1 billion for truck charging. As ever, Tesla is also thinking big. Its commercial truck, Semi, is slowly making its way out of its Nevada facility. Fueling electron-huffing Semis, which are targeting 500-mile ranges, has Tesla purportedly readying Megachargers with up to 1.5-megawatt power. That’s enough, Nelder says, to power a midrise office building, an enormous tech challenge anywhere, let alone desolate trucking outposts from Wyoming to Minnesota. For smaller jobs, Tesla’s ever-tardy Cybertruck, billed as a utility vehicle with sports-car performance, is expected in mid-2023. Tesla has also revived its long-awaited solar promise, including a possible plan for V4 Supercharger stalls on Interstate 8 in Arizona, fed by huge solar arrays, with storage in Megapack batteries.

Musk keeps dreaming and promising.

Tesla’s announced goal of building 20 million cars and trucks a year by the early Thirties seems quixotic even by Musk’s standards. But ask the short sellers: Whether the plan is to dominate global EVs or refill batteries, it rarely pays to bet against Musk.