The first BMW inline-six engine climbed skyward into the shadow of war. By the late summer of 1917, conflict had clawed at Europe for half a decade. Escalations in air-to-air combat were shifting the future of warfare. Each combatant knew that building light, powerful, and reliable airplane engines was of national importance.

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Road & Track.

At an airfield near Munich, that humming BMW prototype prepared to take wing. For the Bavarian company, then just a glom of recently incorporated engine and parts manufacturers, a lucrative government contract hinged on the flight’s success. When the engine roared upward, lifting a German biplane to 16,000 feet in just 29 minutes, its performance was considered breathtaking. BMW did not invent the straight-six; the configuration was widely used in aviation when that prototype flew. The Bavarians didn’t pioneer the straight-six automobile, either. Spyker was first, in 1903, and by 1909 Britain alone held dozens of straight-six carmakers. But BMW is the only major manufacturer to have forged a modern, continuing identity with engines carrying all six of their cylinders in a straight line. And so the company’s history helps illuminate the layout’s abiding strengths, no matter who builds it.

BMW’s 1917 IIIa Flugmotor displaced 19 liters—more than five gallons of churning air and fuel—and produced 226 hp at ground level. It was the brainchild of Max Friz, a designer who left Daimler to pursue his vision for aircraft power. Rather than supercharging or turbocharging, both dicey propositions at the time, Friz bet on high compression, large displacement, and silky six-cylinder thrust.

The importance of that last element is difficult to overstate. Aircraft of the era were a delicate origami of wire, wood, and fabric, and engine vibration often literally shook them apart. The inline six’s inherent smoothness is a function of its layout. When a piston reaches top or bottom dead center, the sudden direction change produces a rocking imbalance at one side of the engine block. In a straight-six, pistons at the front and back of the engine mirror each other’s movement, and these primary forces are negated. So, too, are the secondary forces created by pistons moving faster at the tops of their travel than the bottoms.

Another benefit of inline engines over vees: inline engines are simpler. They require just one cylinder head, and therefore just one valvetrain. Friz’s design proved robust and versatile; both the German navy and his country’s heavy-shipping industry gave BMW’s six their hard-earned approval. Following the IIIa’s promising first flight test, the German government ordered a preliminary, 600-unit run. By October 1918, BMW had cemented itself as a key supplier to the war effort, with roughly 3500 employees tasked with building 150 airplane engines per month. But the war was over by November. Production halted per the Treaty of Versailles, which forbade German aircraft development. For BMW, liquidation appeared the only way forward. The company’s board encouraged investors to sit tight: Farm-equipment manufacturing was needed to rebuild Europe, aviation engines could be repurposed for trucking, the acquisition of a shoe factory might prove profitable. Meanwhile, work on a new six-cylinder aircraft engine had begun in secret. To evade detection by random Allied searches, the blueprints were hidden in the factory’s underground heating conduits.

A secret prototype of that engine was smuggled out to Oberwiesenfeld, BMW’s aviation test grounds, just one year later. The new six powered a biplane there to a world-record height of 31,825 feet. Test pilot Franz Diemer, who wrestled his hunk of wood and wire up to airliner altitudes and temperatures colder than 40 below, reckoned the engine could have gone higher, but he would have succumbed to oxygen deprivation.

The test was a brazen finger in the Allied eye. Shockingly, there was little retribution. In a twist—and possible long-range strategic misstep—authorities granted permission for further altitude-record attempts. BMW’s newest engine, the Type IV, set 16 international flying records by 1926, including the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s flights over the North Pole and Wolfgang von Gronau’s landmark ocean crossings.

Still, prospects in the aircraft business remained bleak. BMW’s board searched desperately for alternatives, banking on truck mills, marine engines, and railroad brakes. In the early 1920s, motorcycle-racing success brought the Bavarians international acclaim and a sliver of stability. That foundation allowed the company to reinvest time and funds in its strength, and for the BMW six to find its forever home: the automobile.

By 1933, a modern template was set. BMW’s first straight-six passenger car, the 303, displaced just under 1.2 liters and produced 30 hp. Racing success followed when a hopped-up version with a hemi head and downdraft carburetors was dropped into the 328 roadster. That engine was a marvel, one of the decade’s best and most resolved, and a source of much of BMW’s prewar prestige. It lasted through the Second World War.

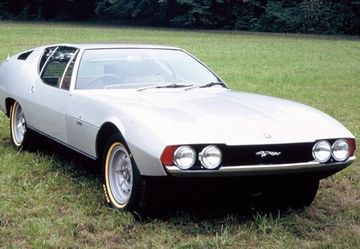

Standout among early postwar sixes was Jaguar’s XK6 (seen at left). This gem was infamously devised during The Blitz, conceived as Jag founder William Lyons and a small team of engineers sat fire-watching on a London rooftop, incendiary bombs crashing around them. (A more perfect automotive example of the British “stiff upper lip” is difficult to imagine.) Lyons was undoubtedly aware of the 328’s success, and Jaguar’s early XK prototypes mirrored the car’s complex pushrod valve gear. His engineers also made advances rooted in earlier BMW engines; the British had raided the German company’s blueprints as retribution following WWI. Jaguar’s new six featured an aluminum-alloy head, dual overhead camshafts, twin SU carburetors, and hemispherical combustion chambers. It delivered 160 hp at 5000 rpm. The design was rooted in racing intent but also acknowledged post-war austerity, pursuing efficiency and fury in equal measure. It debuted in 1948 with Jaguar’s XK120 sports car.

That torch was immediately torture- tested. Lyons, like early BMW management before him, understood the value of marketing hyperbole. Period advertisements feature a laundry list of endurance records set with XK6 power, and notable among the engine’s achievements is proof of its ultimate reliability: 16,582 miles at an average speed of 100.31 mph, a 1952 record set during a week-long, non-stop stint at a French test track. The marque’s record-setting longevity paid dividends—the XK6 was produced and used in one form or another for the next 40 years. XK6 power lived in the E-type, the Mark 2, the XJ, and nearly every other great Jaguar production car through the Eighties. More than 700,000 examples of the engine were built, and the last was stuffed in the engine bay of a Daimler DS420 limousine in 1992. Before that elegant coda, many XKs were utilized in British light tanks and armored vehicles, after passing the military’s strict torture tests, and the engine served in the Falklands, Bosnia, and Iraq.

Of course, other continental inline sixes grabbed their share of history. Mercedes’s oversquare, single-overhead-cam M180 bowed at the Geneva auto show in 1951, then endured through 1985, powering a glut of sedans and the Unimog truck. The similar but larger M198 fitted to the legendary 300 SL “Gullwing” was the first production unit equipped with Bosch mechanical fuel injection and dry-sump lubrication. It even won outings at Le Mans and La Carrera Panamericana along the way.

Across the pond, the straight-six lived an altogether different history. The Beach Boys didn’t harmonize about the world’s most harmonically smooth engine, though maybe they should have; the first Indy 500 victor, the Marmon Wasp, won with inline-six power. But while the V-8 engine stoked American imaginations and aspirations, the straight-six kept busy doing work. “The chief advantage of the six-cylinder car is its smooth running or lack of vibration,” M. T. Richardson wrote in 1906’s Automobile Dealer and Repairer, a Practical Journal Exclusively for These Interests, which was republished in the New York Times. “Constant torque permits the motor to be throttled very low if need be, and it is possible to drive a car slowly in the crowded streets or to change to high speed without changing gears.”

Many of America’s early pickup trucks rode along on a straight-six’s easy torque; all else being equal, the configuration produces torque at lower rpm than a V-8 of the same displacement. The decreased complexity and increased efficiency relative to a V-8 made the six a national mainstay for decades. GM built its second-generation straight-six from 1937 to 1963, a period that included the triple-carbureted “Blue Flame Six” in the first Corvette. Ford’s 300 cubic-inch inline-six lasted from 1965 to 1996, a perennial light-to-medium-duty farm favorite. Chrysler’s Slant Six, which began production in 1960, made a run deep into the Eighties, and the engine’s 30-degree tilt was inspired by the 300 SL’s powerplant. That slanted configuration allowed for a lower hood in passenger cars, and for the water pump to be mounted offset, which shortened the length of the engine. The Slant Six found its way into the Valiant, full-sized Plymouths, and the Dodge Dart, among others, and was sold here until 1987.

When the gas crises of the Seventies and Eighties pressed, transverse inline-fours became the fashion, packed tightly into the noses of front-drive econoboxes. The straight-six grew scarce. Most companies slowly shifted engine production to more compact modular V-6s and V-8s. Jaguar and Mercedes both stopped inline-six production in the latter half of the Nineties. BMW, that early adopter, remained the only mainstream zealot, keeping the layout at the core of its brand. And yet, more companies are reviving the straight-six as they look forward. Turbocharged inline four-cylinders are now the norm in everything from subcompacts to small pickups. The turbo four is compact, efficient, powerful enough—in modern trim, the new Engine of the People, with just one problem: a lack of character and the aural charm of a Disposall chewing wet bark.

Fortunately, the magic of tacking on two extra cylinders remains undiminished. Refinement, torque, and a sense of occasion can still be had. Modular sixes based on those four-cylinders are coming into vogue. Jaguar Land Rover unveiled its new straight-six last year. GM just introduced a new 3.0-liter diesel inline-six for half-ton truck applications, returning to a segment where Ford and Chrysler have chosen to offer vees. And old stalwart Mercedes, after closing eight decades of continuous inline-six service in 1999, returned in 2017 with one of the most forward-looking examples of a straight six ever built.

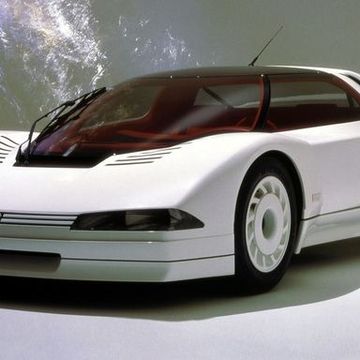

The 3.0-liter M256 leverages the talents of the landmark engines before it while indulging in modern tech and engine packaging. To make the M256 viable in modern cars, Mercedes engineers knew they had to reduce the engine’s length. They did so by adding two cylinders to their existing inline-four, shrinking the cylinder bore (88 mm in Mercedes V-6 engines) to 83 mm to let the cylinders live closer together.

That motor is a multi-talented little wonder. Accessory belts were deleted in favor of a pancake motor (both A/C compressor and water pump are electrically driven) that serves as integrated starter and is tied to a 48-volt electrical system. In AMG models, this furious Frisbee powers an electric auxiliary compressor that behaves like a supercharger and eliminates lag from the engine’s turbocharger. If needed, the pancake can deliver a 160 lb-ft torque wallop directly to the crankshaft. The result is an inline-six’s traditional butter-smooth refinement, taken to its compact, efficient, and cutting-edge conclusion.

This engine marks a return to form for the industry. For decades, conventional wisdom held that better, stronger, and smoother motors sold cars. Surprisingly often, that meant the talents of six cylinders standing next to each other. It’s only fitting, then, that at the twilight of the internal-combustion engine—and, ironically, in what is perhaps its golden age—the eternal inline-six will be there, walking hand-in-hand with electricity, into the automobile’s future.

The only member of staff to flip a grain truck on its roof, Kyle Kinard is R&T's senior editor and resident malcontent. He lives near Seattle and enjoys the rain. His column, Kinardi Line, runs when it runs.