For last week's column about the brilliant Alpine A110, I spoke with the car's chief engineer, David Twohig, and the subject of steering came up (as it often does among enthusiasts). The A110 has excellent steering, perfectly weighted, offering the driver clear lines of communication about what's happening at the front tires. It's also electrically assisted.

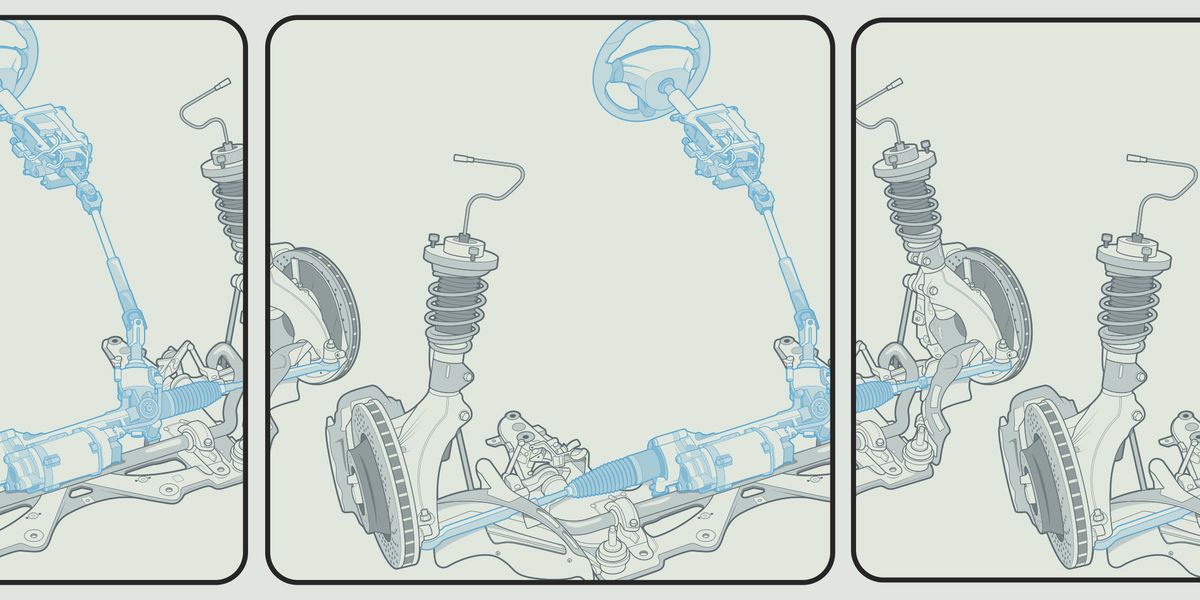

That's an interesting point. Electric power-assist steering (EPAS) has been controversial among enthusiasts. An EPAS system uses an electric motor on the steering shaft to help the driver turn the wheel. These motors tend to dampen out steering feel, especially the high-frequency vibrations that come up through the tires, because the motor has to speed up and slow down every time the wheels move side to side. (Which is, of course, all the time.)

Obviously in a manual steering system, there's none of this damping effect because there's just shafts, a rack and pinion, tie rods, and tires; the same is true with a hydraulic power-assist system, which adds a (typically engine-driven) hydraulic pump to reduce steering effort. One might think manual steering is the best in terms of feel, and hydraulic is second. The reality is quite different.

The A110 has an interesting contrast in the Alfa Romeo 4C. Both are very lightweight, mid-engine sports cars with small-displacement turbocharged four-cylinders and dual-clutch gearboxes. The Alfa uses a carbon-fiber monocoque while Alpine makes the A110 from aluminum, but both weigh about the same and offer similar performance. A big difference is that the 4C has manual steering. When we first heard this we rejoiced. When we finally drove the car, we were very disappointed. Typical of non-power systems, the 4C's steering is extremely heavy at low speeds, but the big issue is that it feels vague. On top of that the car is darty.

What a driver feels in the hands isn't just the product of the assist system, or lack thereof. As we've explored previously, front-suspension geometry has a huge effect on steering feel, and there's a number of other factors, like tires, weight over the front axle, and more.

Some traditional enthusiast cars didn't handle the transition from hydraulic to electric assist well. Turning the steering wheel was met with a weird numb sensation, almost as if the wheel isn't actually connected to the tires. This led a lot of enthusiasts to write off EPAS completely, lamenting a supposed death in steering feel. This, of course, is not the case. Sure, the first BMW 3-Series with EPAS didn't steer as nicely as its predecessor and the same is true of the first Porsche 911. But, there are other reasons for this.

Twohig told me that the team at Alpine considered manual steering at first, but after driving the 4C, they quickly decided that wasn't the way to go. Alpine engineers also found that the 4C's front suspension geometry was very compromised, with a kingpin angle of nearly zero. The steering axis, also known as kingpin inclination angle, is the axis about which the wheel steers. In the 4C, the steering axis is nearly vertical, and generally speaking, cars with a near-vertical steering axis have vague on-center steering feel, and not much self-centering torque, which contributes to the nervous feeling. "We knew early on we weren't going to make that mistake, and we were going to have power assistance," Twohig said. (I've heard that tweaking the alignment can really help the 4C, for what it's worth.)

Beyond the A110, there's a number of new cars that steer as good as anything, all with EPAS. The Mazda MX-5 Miata, the Honda Civic Type R, and basically all current Porsche sports cars (things have changed a lot since the first 991) jump out as having extraordinary steering, to the degree that most enthusiasts might not even know that they use electric assist.

These cars sweat the details on suspension geometry, tire choice, and assistance motor. The A110 uses double-wishbone front suspension with great geometry. Twohig also pointed out that by the time the A110 arrived in 2016, Alpine parent-company Renault had 14 years of experience with EPAS, debuting a system on the second-generation Mégane hatchback. Honda's had even more experience. The 1991 NSX was the first production car to use EPAS, though until 1995, it was only fit to automatic-transmission models, and even afterwards, it was deleted for special editions like the 1997 Zanardi and the 2002 NSX-R. The Honda S2000 also had EPAS. So it's no wonder that a Civic Type R built over 30 years later has great EPAS.

"There have been improvements made right across the patch, from input sensors (steering angle sensors), to the actuator (the motor), output sensors (motor position and torque detection), but also the ECU speeds, and the sophistication of the control software," Twohig says. "And we're not even touching on improvements to the mechanical package: Location of the motor, stiffness of the system etc."

An electric system is cheaper, safer, simpler, and more reliable than a hydraulic system, and it offers far more tuning capabilities and enables safety features like lane-keep assist. One of those tuning capabilities is the ability to filter out certain steering behaviors. Perhaps customers don't want the steering wriggling in their hands. EPAS may naturally dampen some of those high-frequency inputs, but automakers can choose to use the motor to filter out even more.

EPAS by its very nature isn't inherently bad, especially when you consider the generational improvements made to the systems. Ultimately, though, good EPAS comes from automakers that prioritize good steering. In the transition from E90 to F30 3-Series, it's not just that BMW switched the assistance type, it took a different approach to how its steering felt.

This might've been borne from a desire to improved safety. In a 2019 column, former R&T contributing editor Jason Cammisa contrasted the great steering feel of the Shelby GT350 to the numb last-generation M2. The M2, like many BMWs, used a relatively large motor within the EPAS system. Generally speaking, the greater rotational inertia of a bigger, more powerful motor leads to a greater damping effect. A BMW engineer told Cammisa the company's internal standards for how quickly a driver is able turn the wheel lock-to-lock necessitates a larger EPAS motor. This motor may dampen feel, but it enables the driver to catch the car quickly in a slide. By contrast, the GT350 had a relatively small motor, and thus better feel, but Cammisa found it was almost impossible to countersteer quickly enough during a drift.

That brings us to a more fundamental argument about what is good steering? Is it feelsome, or is it safe? That's a big question, though. One for another day. (I also want to note that BMW steering feel has improved much in the EPAS era, especially in the latest M cars.)

EPAS is here to stay, though that will change if and when steer-by-wire becomes the norm. Even McLaren's excellent hydraulic systems use an electric motor to drive the pump as this doesn't produce any drag on the engine, and allows speed-dependent variable assist. And McLaren engineers will be the first to tell you that the company's choice to use hydraulic steering is a more expensive option.

This isn't a reason for lament. Instead, if an EPAS car has bad steering or bad steering feel, recognize and lament the fact that this has to do with approximately one billion other choices an automaker has to make.

A car enthusiast since childhood, Chris Perkins is Road & Track's engineering nerd and Porsche apologist. He joined the staff in 2016 and no one has figured out a way to fire him since. He street-parks a Porsche Boxster in Brooklyn, New York, much to the horror of everyone who sees the car, not least the author himself. He also insists he's not a convertible person, despite owning three.