They say it always rains at Le Mans. At least, that’s what 100 years of soggy racing shoes would suggest. But 100 years ago, at the first running of the world’s marquee endurance race, there was no such expectation.

This story originally appeared in Volume 16 of Road & Track.

Firstly, it did not rain. Well, not right away. Instead, hail rattled like Maxim fire against the fragile bodies and veneer-thin windscreens gathered in rural France. Under those angry skies, on the 26th of May at 4:00 p.m., the flag fell on the very first daylong torture test on the roads near Le Mans, France.

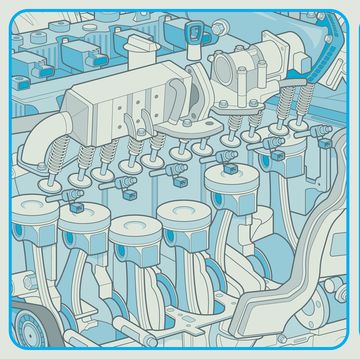

The 1923 event was conceived as a demonstration of production-car durability and featured vehicles equipped with fenders, running boards, rearview mirrors, and horns. Vehicles with anything larger than an 1100-cc engine had to have four “comfortable” seats. A field of 33 cars started. Of those, 30 were French-built. Only two of the carmakers survive today: Bentley and Bugatti. The event’s organizer, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO), might have had international aspirations, but those first years were French provincial affairs. The event’s regulations were an impenetrable bramble, but one thing was clear: This was not a race. Or it wasn’t until the flag dropped. The front-runners—three Chenard-Walckers and the single Bentley 3-Litre Sport—were tearing ass through the rolling countryside.

Le Mans became a race.

Or maybe it was war. From 10,000 feet, the original 10.7-mile circuit traces a similar line to the modern track. But at ground level, la Sarthe looked more like a trench at the Somme. The “roads” in rural France at the time were mostly narrow dirt lanes. The hail and the rain that inevitably followed turned them to rock-studded muck.

The racers soldiered on.

When a rock punctured the fuel tank of John Duff’s Bentley and he ran out of gas on the circuit, he somehow navigated back to the pits on foot. His teammate, Frank Clement, commandeered a police bicycle and ran la Sarthe against race traffic with two gas cans slung from his neck.

The French army aided the drivers by setting up acetylene floodlights, the polished reflectors of which look, in period photos, like tiny trackside UFOs. The lights bathed la Sarthe’s tightest corners in a warm glow. Between the blat of engine noise and diesel generators, spectators enjoyed classical music played over shortwave radios, the tunes broadcast from the Eiffel Tower herself. A proto–hospitality tent, where all drivers were welcome to dry off and rest, went through 150 gallons of soup, 50 chickens, and—this being France—450 bottles of champagne.

Because of the aerodynamic advantage, most cars ran with their windscreens folded down. And yet, most of the drivers of these open-top racers did not wear goggles. Head protection consisted of cloth “helmets.”

A shocking 30 of the 33 starters finished the first Le Mans. Clement set the event’s first lap record in the Bentley, covering la Sarthe’s 10.7-mile distance in 9 minutes, 39 seconds. The “winning” Chenard-Walcker covered 128 laps in 24 hours. And what did the winning team win? Nothing but the Rudge-Whitworth Triennial Cup. Well, a third of it. The ACO devised the first Le Mans as one part of a three-year endurance test to be run annually. Competitors’ average speed and total distance were weighed against a complex classing formula that accounted for engine displacement. The ACO’s logic was that if it forced entrants to return the next year to defend their honor or grasp for victory, they’d at least come back. And for the most part, the ACO was right.

One hundred years later, 1923 seems both foreign and distant. But a couple of things remain constant at Le Mans, certain as the sunrise: the brutal toll on man and machine, and the rain.

The only member of staff to flip a grain truck on its roof, Kyle Kinard is R&T's senior editor and resident malcontent. He lives near Seattle and enjoys the rain. His column, Kinardi Line, runs when it runs.