In Northern Ireland, on narrow roads flanked by unyielding stone, the motorcycles fly. The bikes are out of their element, ripsaw racing machines of furious speed, bucking under power and rising into the air over undulating pavement, struggling against the confines of public roads closed for the race. The riders commit, knowing the danger but in the moment conscious only of the speed.

At this year’s F1 race in Baku, Azerbaijan, the cars of Max Verstappen and Sergio Perez hit 215 mph. Road-racing motorcycles will brush up against or exceed that speed - on country lanes.

Clutching their programs, spectators cluster at the stone fences as the bikes scream past, machines and riders briefly taking flight. Ordinary young men and women – farmers, couriers, mechanics, truck drivers – on the knife-edge of human ability. Gray-hairs in leathers recounting past legends over a pint in the pubs. A community.

But, on the evening of Thursday, February 9th of this year, following an emergency meeting, the Motorcycling Union of Ireland issued a declaration. Insurance companies had been hard hit by the pandemic, and were minimizing risk exposure. With liability insurance costs unexpectedly surging to more than three times as much as to cover events in 2022, there was simply no way forward.

All road-races in Northern Ireland were hereby canceled. In 2023, said the MCUI statement, there would be no motorcycle road-racing in Ireland. It would mean the end of one of the fastest forms of motorsport, one of the deadliest. An end to a century of tradition.

On the third of May, 1921, by order of the Fourth Home Rule Bill passed by the UK parliament, Ireland was partitioned into north and south. In the twenty-six counties south of the border, the aftershocks boiled over into a nasty little civil war, the violence seen lurking at the edges of The Banshees of Inisherin. Things were also bad in the six counties of the newly-formed Northern Ireland, long-running sectarian troubles still not fully healed today. But, less than three months after that partition, the people of the north went road racing.

They were pirates, really. With no permission from local authorities, the motorcycles gathered at Killough, at Ballynahinch, at Bannbridge, and the Temple crossroads. Relying on friendly local police to clear roads and shoo spectators out of the way, the motorcycle clubs of Northern Ireland pitted Nortons against Harley-Davidsons, lapping between the hedgerows as quickly as they could. By October, officials were furious.

One rider, competing in both sidecar and solo racing, bent his handlebars out and in to clear the sidecar. Metal fatigue reared its head on the third lap of a 10 mile course, the bars broke and he crashed into a bank. A local farmer cut a length of holly, they splinted the bike back together, and he completed the race before riding the long road back to Dublin.

Madness! But a persistent, enduring madness, one that has grown from law-flouting recklessness to a hundred-year history of motorsport. Across the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man has been conquered again and again by riders from Northern Ireland; a statue on the mountain course pays tribute to a man from Ballymoney crowned King of the Roads – Joey Dunlop. The Superbike World Championship was also dominated by a Northern Irish rider, six-time champion Jonathan Rea, who is still the winningest-ever competitor.

And in Northern Ireland itself, a plethora of races, from the crown jewel that is the North West 200 to the Cookstown 100, celebrating its 101st birthday. Or the Ulster Grand Prix, a 7.4 mile course with a record average speed of 136.4 mph edging out the Isle of Man TT for title of the world's fastest motorcycle road-racing course.

The story the outside world mostly knows of Northern Ireland is that of divided communities, of the shadow of the Troubles. For the people who actually live here, there is another story, a heritage, a community.

“My earliest memories of racing are traveling to road races in a car with my dad and sister. We traveled the length and breadth of the country to every road race and most of the time pitched a tent for the weekend in the paddocks amongst all the riders and teams and I suppose that's where I got the bug for it.”

Gary McCoy is coming off a fifteen hour shift driving a truck up the length of Ireland on rain-slicked roads. A champion short circuit rider, he was awarded Newcomer of the Year at last year's Northwest 200.

“The smaller road races definitely make it easier for younger riders to get into the sport and get a feel for it,” says McCoy, “You have to cut your teeth for a few years circuit racing first. So between the circuits and the smaller road races it builds you up for the bigger events like the Northwest 200 and the Ulster Grand Prix.”

The Northwest 200 and the Ulster Grand Prix are marquee events that rival the Isle of Man TT. More than a hundred riders compete, with average spectator attendance listed at between 150,000 and 200,000 over the race week, 100,000 on race day itself. Though these are merely estimates, since no-one needs buy a ticket to watch. The races get by on selling racing programs, but many spectators simply tramp through a field to lean against a stone fence to watch.

These big events attract big names: TT racers John McGuinness and Guy Martin as recent examples. The tradition stretches long into the past, and includes times when cars were also raced at these circuits. In 1933, for instance, you could have walked over to the Ards street circuit just west of Belfast, and seen Tazio Nuvolari take the win at the Ulster TT race of that year.

But it's the smaller road-races that are the heart of Northern Ireland's road-racing culture. These are grassroots races, held in places like Cookstown or Tandragee, the latter famous for the Tayto potato chip (called crisps here) factory. As an aside, the Republic of Ireland also has its own Tayto company, and there is a rather heated North vs. South debate about which potato-based snack product is superior.

Canadian motorcycle journalist and circuit racer Mel Gantly competed in the Tandragee 100 support races in 2018. When asked if he'd go back to race again in Northern Ireland, he doesn't even let me get the question fully out.

“Yes!” Gantly interjects exuberantly. He explains the feeling of being an outsider at these races. “I was lining up at the start, nervous, and the other riders were saying, 'You're already a road-racer. You're here – you're one of us.'”

Gantly ran his newcomer's laps under the watchful eye of Northern Ireland's Davy Morgan, a veteran road racer who lost his life last summer at the Isle of Man TT. It was Morgan's 80th TT start.

Road-racing is probably the most dangerous of all motorsports. Since the first Isle of Man TT races in 1911, some 265 riders have lost their lives in crashes on the course, six of them dying in the 2022 running alone. In the past 50 years, 22 riders have died at the Ulster GP, and 14 at the Northwest 200. These figures compare to 32 driver deaths in Formula One racing weekends since 1950. But for many veteran riders, the itch never fades. It's not just youthful recklessness, but a primal need that never fades.

It's the kind of sport where you often lose your heroes. Gary McCoy sends me a small, low-resolution photo of himself as a chubby-cheeked small boy – in Ulster terms, a wean – at the NW 200 twenty-three years ago. Crouching down with him and smiling at the camera is a smiling, gray-haired man who, at the time, is just months away from his death.

Joey Dunlop will forever be the King of the Roads. He will also forever be “Yer Maun,” the catch-all term Northern Irish people use in a rough approximation of you-know-who. He was a staggering talent possessed of preternatural ability, and also a skilled and thorough engineer. But he was also just Joey, born in a Ballymoney cottage where there was no running water. A soft-spoken country boy, but a hero in the making.

Twenty-six Isle of Man TT victories, the most of any rider, and the last hat-trick of wins achieved at the age of 48. Formula One motorcycle racing champion every year from 1982 to 1986. NW200 winner 13 times. Ulster GP champion 24 times.

And for all that, Joey was a shy and ordinary-seeming man, not a whiff of superstar about him. Once, he was invited as a guest of honor to a motorcycle show in Birmingham. Fellow racer John McGuinness found Dunlop patiently waiting in line to buy a ticket.

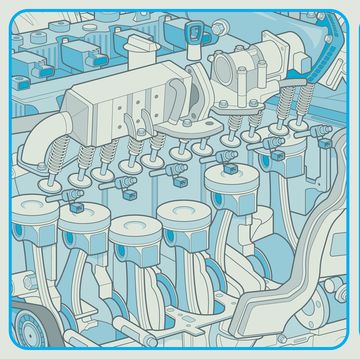

In the 1970s, Dunlop was a scruffy youth scrounging for parts to get an old Triumph Cub to run. Those who knew him then called him an oil slick in racing leathers, perpetually covered in engine grease, long-haired and disreputable looking. His talent spoke for itself, and before long Honda came calling. By the 1980s, no one could touch him.

And yet, at the same time, Dunlop never stopped being that oil-spattered youth. Picture the horror on the faces of Honda senior engineers when this wee Ulsterman insisted on fiddling with the inner working of their pristine factory racing bike. And imagine the consternation when Dunlop would just tip the bike over on the paddock grass to make adjustments.

Because he had to trust in the machine, and the work of his own hands. In the race, man and motorcycle would operate as one, as though they had exchanged atoms. He was astonishing to watch, and if you were even on the very fringes of motorcycle road-racing, Joey Dunlop was your hero. In a larger sense, he was all of Northern Ireland's hero.

Killed in a racing accident in Estonia, in July of 2000, Dunlop's funeral in Ballymoney was attended by some 50,000 people. Today, the most successful rider at the Isle of Man TT is awarded the Joey Dunlop trophy.

Joey's nephew is the hard-charging Michael Dunlop, the first rider to complete the Isle of Man Snaefell mountain course in under seventeen minutes. At 34, the younger Dunlop has 21 TT victories of his own. But the Dunlop clan has taken a heavy toll to become Northern Ireland's best-known motorsport dynasty. Michael's father, Robert, was killed in racing practice crash in 2008. Older brother William Dunlop died in a crash ten years later at the age of 32.

Road-racing is an unforgiving sport. The consequences for error or mechanical failure are immediate and often fatal. The riders accept this, but running these events is becoming far more difficult in terms of risk and liability.

Certainly any discussion of the future of the Isle of Man TT hints that there may come a time when the deaths are no longer acceptable. There are few ways to make road-racing actually safer; putting machines capable of such speed in an unyielding environment is just inherently risky. “The furniture,” as riders call the stone fences and trees, simply can't be moved to create runoff.

But there is a mountain that has killed more people than Snaefell. Since the first summit of Mount Everest in 1953, some 310 climbers have perished in the attempt. Challenging yourself against an unforgiving environment is part of the human experience. Road-racing is not a bloodsport, it is – like mountaineering – risk at the highest level in pursuit of a reward. For Everest, the appeal is obvious: conquering the highest mountain in the world. The rewards of road-racing seem more nebulous, hard for the riders to explain. But harder still to resist.

The skyrocketing insurance rates for Northern Irish road-racing seemed to signal not just the end of road-racing in Ulster, but the approaching end for the Isle of Man TT. But, as it happens, at the eleventh hour, a deal was struck.

Thanks in part to a crowdfunding campaign that raised some £90,000, and a new lower insurance quote, the MCUI announced last month that most of the races would return to the calendar. The first of these, the Cookstown 100, saw wet and slippery conditions. Michael Dunlop set the fastest lap and placed second in the Supersport class. Ballymena racer Barry Davidson marked his thirtieth year of racing with a milestone 100th win.

It was a return to a hundred year old tradition. Motorcycle road-racing is part of the soul of this place. It is pure, it is dangerous; it is steeped in history, it is exhilaration in the instant. The specter of death always looms close. But the racing is a people’s way of life.

The 2023 running of the Northwest 200 is held the week of May 7-13, the crowds descending in their thousands. Alastair Seeley, a 43 year-old rider from Carrickfergus, will be racing a BMW1000RR there. The NW200 is his only road-racing event on the calendar, and since 2004 he has won there 27 times. On Tuesday, Seeley put his BMW on pole in the Superbike class during practice, hitting a top speed of 207 mph in patchy rain the day before. Just behind him on the grid is Michael Dunlop on his Honda. Race day is this Saturday.

“Racing's always been in the blood,” Seeley says. He talks about boyhood days when his father – also a road-racer for a time – would take him to the Ulster GP. “I remember... being in amongst trees and me and my friend would scribe our names on the trees. Whereas my dad would be fully focused on watching the racing, we watched a bit of racing when it came on and then the breaks in between we would be messing about.”

It's the rural Ulster poetry of Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, a snapshot of everyday country living shot through with flashes of rider and machine.

“Everybody's a close knit family in it,” Seeley says, “We all know the dangers, and we respect each other as riders. Everybody's there to help each other. There's never any issues with religion, or people being biased or anything like that in the whole Northern Ireland thing.”

“It's definitely completely forgot about when we go road-racing.”