I first went to Le Mans as a journalist in 2015 as a guest of Nissan in what would be an ill-fated year.

This story originally appeared in Volume 16 of Road & Track.

I slept in a six-by-eight-foot storage container stacked on the loge level of the Stade Marie-Marvingt, the 25,064-seat home to Le Mans Football Club right inside Tertre Rouge, the turn that sets up the blistering rocket ride of the Mulsanne straight. When I arrived at the stadium, I was given a rudimentary Nismo-branded shaving kit and a pair of red tartan paper slippers to wear to the bathroom. I had a cot to sleep on, if I chose to. While the door locked, every sound within 10 kilometers reverberated inside the bare steel walls.

Even as the sprawling infield of Le Mans filled with people during race weekend, the stadium was empty except for us wretched writers, padding to and from the stadium urinals in our paper slippers.

As reporting trips go, this wasn’t the worst. In my career, I’ve been chased out of a Sinaloa village by cartel thugs working for a local parish priest, and I lost a molar when a 12-year-old paint huffer jammed the muzzle of a pistol into my mouth in Brazil. Those were unpleasant reporting trips.

This trip sucked at first but redeemed itself. Because unlike, say, a Formula 1 race, Le Mans isn’t about hotels and caviar. It’s a carnival, a bacchanal, a free-for-all. It’s a place where it’s okay—really, man, just do it—to piss in public after a few drinks. Some years Le Mans is a peaceful Bonnaroo, some years it’s Burning Man, and some years have a touch of Fyre Festival (complete with storage unit and paper slippers). The quantity of alcohol consumed is staggering and unrelenting, even by English standards. Your state of dress comes to resemble your state of mind.

I’m sure there are hotels and caviar for the snot-nosed elites, wherever they’re hiding. But that’s not the essence of Le Mans. Le Mans would be a blue-collar orgy if everyone weren’t passed out from drinking too much cheap wine.

The race tests your camper van, port-a-potty, and cell service. Imagine a 24-hour Kentucky Derby where a 300-pound English electrician in a preposterous derby headdress sits in the rain and drinks the village dry to ease his discomfort.

In 2015, my pain wasn’t just that I was housed in a steel container in the bowels of a football stadium. It was the 83rd running of the race, and Porsche was jousting with its cousin Audi for LMP1 dominance. Notably, my host was Nissan.

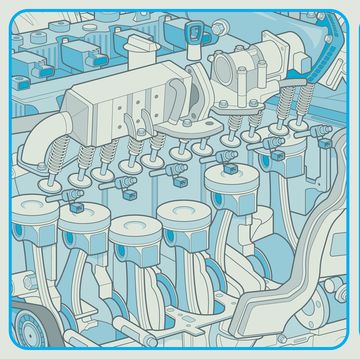

Nissan had commissioned certified motorsport weirdo-genius Ben Bowlby (he of the brilliant and disastrous Nissan DeltaWing), who had devised, built, and unleashed—at Le Mans, of all places—a half-baked front-engine, front-wheel-drive LMP1 that wedded a twin-turbo V-6 with a flywheel-based hybrid system, which would theoretically send power to the rear wheels. It was supposed to push out between 1500 and 2000 hp, but it didn’t come close. This Brobdingnagian idea was a loathsome betrayal of the principles of simplicity that often characterize great endurance racing cars, and it failed. Power never made it to the rear wheels, not for a single lap, and the drivers pushed three shopping carts around the Circuit de la Sarthe at 20-plus seconds per lap slower than the leading cars.

At that moment, having escaped the dismal black noise swirling inside the empty soccer stadium, I sat with a handful of writers in Nissan’s paddocks, awash in the flop sweat of Nissan executives. I took no pleasure in their pain. I love risk and always respect race teams that push the bounds of reason just because; I also love the way Bowlby would jump off a cliff chasing an interesting notion, and a whole phalanx of auto execs would counterintuitively jump with him. I wish the damned idea had worked.

And so, as dawn broke over the trees, the race entered the morning groove and accelerated to its end—an anticlimactic procession of cars following the one-two finish by the Porsche 919 Hybrids. Eighteen hours had passed since the start.

So I went in search of the underground, the demimonde of Le Mans. Beyond the beer halls and merch trucks, campgrounds peppered the landscape. I saw men in suits sleeping in the muck, holding empty beer steins in a comatose vise grip. There were teenage couples on blankets, half dressed and wet from the rain that swept through at 4:00 a.m. but perfectly content. Tents lined the berms overlooking Indianapolis, and the smell of frying bacon drifted from camper vans. Trash was strewn everywhere. There was no pop music, just the rock ’n’ roll of the prototypes and sports cars ripping past in the morning light.

Back at the stadium after the finish, the Nissan team was quietly polite as we handed over our paper slippers. “Better luck next year,” I said. Not likely.