“They will just have to be bigger!” he shouted.

“But, sir, they can’t be bigger!” the other man replied, panicked. “The wheels are 16 inches, and those are the biggest wheels we have. You can’t fit 17-inch brakes inside 16-inch wheels, sir.”

“Who says brakes have to fit inside the wheels?”

This story originally appeared in Volume 16 of Road & Track.

I wasn’t alive in 1952, when Briggs Cunningham and his team developed the C-5R, an open-topped road racer, for the 24 Hours of Le Mans, but I imagine this is how the conversation went. Cunningham got his 17-inch drum brakes; they are mounted inboard of the Halibrand magnesium wheels. Sure, disc brakes were the more compact, elegant solution. But at that time, only Dunlop made disc brakes, reserving them for Jaguar.

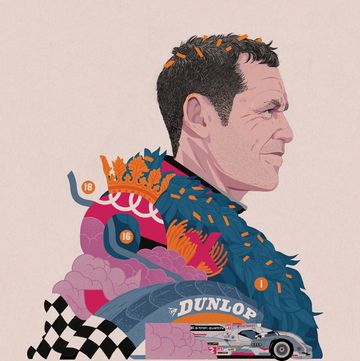

The only thing more American than starting a privateer racing team to take on the big-bad manufacturers (see heroes Shelby, Haas, Glickenhaus) is doing so using dead-reliable, low-tech, proven hardware. Ergo, Cunningham was the most American privateer, the first to stand proudly on the Le Mans podium with his own name on the car.

Cunningham was a racer first and manufacturer second. His motorsport career began, as many do, in other people’s cars. He owned and raced Buicks, Cadillacs, Ferraris, and Healeys, modifying them for racing in creative and innovative ways. He transplanted engines from one car into another, such as his Cadillac V-8–powered Healey. Or he would fit custom coachwork onto production vehicles, like the legendary Cadillac “Le Monstre,” a ghastly and amateurish-looking—but brutally effective—speedster-style body draped over the standard 122-inch-wheelbase chassis of a luxurious 1950 Series 61 Club Coupe.

The total output of the B.S. Cunningham Company of West Palm Beach, Florida, was either 34 or 36 cars, depending on who is counting. The C-1 prototype led to a pair of C-2R race cars, which appeared at Le Mans in 1951. Subsequently, Cunningham built either 25 or 27 C-3 road cars, essentially streetable versions of the C-2R. The C-4R and C-4RK raced in 1952. Production of those models totaled three.

For the 1953 running of Le Mans, Cunningham prepared a single C-5R roadster. I’m watching it roll off a transporter at the Concours Club, a private racetrack and high-end hangout in Opa-locka, north of Miami and 65 miles from where the C-5R was hand-built 70 years ago. This car, now owned by the Revs Institute, was the only Cunningham racer to earn a spot on the podium at the 24 Hours, taking third behind a pair of

Jaguar C-types.

Cunningham built just a single C-6R, probably his prettiest design, which looks like a Jaguar D-type that’s slipped into a white tuxedo. It boasted a best average lap 13 mph slower than its C-5R predecessor, which spelled the end for Cunningham as an independent builder.

Like other Cunningham designs, the C-5R is awkward and inelegant but purposeful. The grouper-esque mouth wraps around the nose of the car, feeding a pair of brake ducts and the simple cooling system utilized by the 331-cubic-inch Chrysler “FirePower” Hemi V-8. The bodywork is designed for a taller driver to hide within, which would make sense if there were any appreciable legroom. As with other early postwar race cars, aerodynamic stability was developed through trial and bloodshed. In profile, this car looks an awful lot like an airplane wing. Whatever. It was the fastest car down the Mulsanne straight that year, clocking 154.81 mph.

Opening the clamshell bonnet reveals a variety of interesting engineering choices. The brass radiator is roughly the size, shape, and style one might find on a narrow-nosed luxury car from the Thirties. The chassis rails look right out of a late-Forties Kurtis Kraft Indy car. Unlike earlier Cunninghams, the C-5R made do with a solid front axle, an odd choice for road racing. The Chrysler V-8, with its double-deuce carbs, makes 310 hp thumping along at 5200 rpm. Drivers John Fitch and Phil Walters were advised to upshift at 4500 during the race. At about 2500 pounds, the C-5R has about the same weight-to-power ratio as a C8 Corvette, though without the benefit of a modern transmission. Cunningham used an unsynchronized Siata truck box—apparently, the only thing around that would survive under the Hemi-headed “FirePower” torque.

Then there are the C-5R’s unmistakable brakes, the largest drums ever mounted to a sports car. Ultimately, it didn’t matter how big they were. The Cunningham’s drums couldn’t match the Jag’s discs. Still, no Cunningham-branded car ever finished better at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and now, 70 years later, I get to have a go.

Thanks in part to the car’s simplicity and the Revs Institute’s commitment to keeping all its cars ready to drive, the C-5R works perfectly. It fires to life on the first crank with a cherry-bomb blast from the twin rear-exit exhaust. It idles smoothly and has a relatively light clutch. The ergonomics, at least for someone of larger stature, are horrid, later proved by my extremely sore right leg and the black rubber streak the steering wheel embedded on the thigh of my jeans.

The car is simple but not easy to use. Everything must get up to temp to work properly. The cold tires are not quite round. The cold brakes tug the front end to and fro. And the cold gearbox makes a disconcerting crunch, despite that I do my very best to shift smoothly. Even with a track all to myself, it is impossible to separate the physical car from what it means. Every braking zone, I think, “One of one, $10 million.”

After five or six laps, the car starts to behave consistently. It brakes straight and true. The crunching from the gearbox subsides. The suspension settles, and the engine makes big, easy power. The three-four shift requires barely a lift of the throttle, and crossing the kink at 100 mph is smooth, effortless, and rewarding, as is the four-three downshift that follows. Long straights and high-speed sweeping bends are this car’s comfort zone. On a small, tight course like this one, it’s a real workout. How ironic that very light cars are often burdened with such heavy controls. Though I’m clearly not going full-on racing pace, I work up to speed and briefly stop thinking about how irreplaceable the car is.

We use every minute of the allotted track time, mostly for photography. When the director yells “Wrap!” with six minutes left on the clock, I eke out three more laps as fast as I dare. I finally get it: The truck box operates smoothly under full throttle and heavy braking. The suspension loads up beautifully and is talkative at the limit. Legroom improves when your right foot mashes the pedal into the floorboard.

The C-5R didn’t beat Jaguar, but it provided the benchmark for American privateers. It used simple, homegrown tech that was overbuilt and understressed. Only the bravest souls would dare race something this light and dangerous. And even then, they’d demand bigger (and better) brakes.